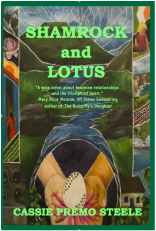

"A wise novel about feminine relationships and the triumph of the heart."

-Mary Alice Monroe, New York Times bestselling author of The Beach House

"Steele, who is also a poet, laces this story with poetry, legends, history, and delicious food. This is an impressive fiction debut."

-Suzanne Kamata, award-winning fiction writer and author of The Mermaids of Lake Michigan

Excerpt from Shamrock and Lotus by Cassie Premo Steele

There are some things, Padmaj had learned, that are best done alone, no matter how painful.

As he lit the candle on the altar in the twinkling darkness, his hair still wet from the bath, his eyes rested on Ganesh, the elephant god who could banish all obstacles.

Open all doors.

Padmaj sat down on his mat, in the lotus position, and closed his eyes gently, and let his mind focus on an inner image of a door.

He had seen many open doors during his lifetime.

The open door of the region’s ancient mosque that allowed his mother to attend the funeral of the last living Muslim woman in their village.

The open door of his mother’s heart that allowed his father back in after an absence of seventeen years.

The open door of his mother’s womb that allowed his father’s seed to take root there.

The open door of the hut where he lived with his mother, which his father walked back and forth through, again and again, during the first three years of Padmaj’s life.

The open door his father left behind, for the final time, leaving Padmaj and his mother to cling to each other, in sorrow.

The open door the white man walked through, when Padmaj was eight, leaving him with a memory he was still trying to forget.

The open door his mother pushed him through when he was twelve, sending him to Lucknow for school, where he learned French and proper English and excelled especially in the memorization of the poetry of the Celtic Twilight.

The open door of the airplane that took him to America, at eighteen, for college in a city called Boston where, he’d learned in school, the War of American Independence had begun.

The open door of the white envelope that his mother handed to him at twenty-three, which enabled his move to Ireland and the down-payment on the restaurant, which he now owned outright. Himself. Independent.

The open door of the restaurant, over which he hung colored beads, reminding him of the colors of the world he had seen with his own eyes—the red of the shuhag he never saw his mother wear on her forehead and of the blood that he did; the orange of the sun that he had seen set in the west of three continents; the yellow of ghee and of McDonald’s french fries which he had secretly come to love; the green of the trees on his mountain home and of Ireland’s grassy hills, the blues of the Indian ocean and of Claire’s eyes.

He stopped, opened his eyes, looked at Ganesh again, the ugly, large-nosed elephant man who reportedly made a wonderful lover.

Why were Claire’s eyes entering his mind?

What did they have to do with doors, with open doors?

He closed his eyes again, tried to concentrate.

He saw Claire there, again, with the blue of her eyes through the words of the poem he had memorized as a student in Lucknow, when he was just beginning to learn about love, in his own body:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

He heard Caitlin stirring in bed and opened his eyes again, and then shut them quickly out of a sense of guilt at having allowed Claire to enter his thoughts like this, during his meditation, on this day so obviously full of anxiety for Caitlin that he could see it on her face already, through the dim blue light before dawn.

He skipped purple and went straight to white to complete his meditation, remembering the white on white embroidery his great-grandmother did, which she continued to do even up until the day of her death, the stitchery so delicate that it might have been done by the tiny translucent spiders that lived in the crevices of the bark of the oldest trees in the forest.

He then sent a blessing to those spiders and those trees, and to his great-grandmother, his father’s mother, and another to his mother’s mother, also in the spiritworld, and to his own mother, and to all his aunts, and to all the mothers he knew, including Claire, and Caitlin’s mother, whom he had never met but who, he knew, could probably use some extra blessing on this day.

And he finished by giving light to Caitlin, who was not a mother, and so lacked the wisdom of one; he prayed that the water surrounding her now in the shower would stay with her all day and into the night, as protection, as comfort, as something clear and pure and clean and white and full of wisdom.

There are some things, Padmaj had learned, that are best done alone, no matter how painful.

As he lit the candle on the altar in the twinkling darkness, his hair still wet from the bath, his eyes rested on Ganesh, the elephant god who could banish all obstacles.

Open all doors.

Padmaj sat down on his mat, in the lotus position, and closed his eyes gently, and let his mind focus on an inner image of a door.

He had seen many open doors during his lifetime.

The open door of the region’s ancient mosque that allowed his mother to attend the funeral of the last living Muslim woman in their village.

The open door of his mother’s heart that allowed his father back in after an absence of seventeen years.

The open door of his mother’s womb that allowed his father’s seed to take root there.

The open door of the hut where he lived with his mother, which his father walked back and forth through, again and again, during the first three years of Padmaj’s life.

The open door his father left behind, for the final time, leaving Padmaj and his mother to cling to each other, in sorrow.

The open door the white man walked through, when Padmaj was eight, leaving him with a memory he was still trying to forget.

The open door his mother pushed him through when he was twelve, sending him to Lucknow for school, where he learned French and proper English and excelled especially in the memorization of the poetry of the Celtic Twilight.

The open door of the airplane that took him to America, at eighteen, for college in a city called Boston where, he’d learned in school, the War of American Independence had begun.

The open door of the white envelope that his mother handed to him at twenty-three, which enabled his move to Ireland and the down-payment on the restaurant, which he now owned outright. Himself. Independent.

The open door of the restaurant, over which he hung colored beads, reminding him of the colors of the world he had seen with his own eyes—the red of the shuhag he never saw his mother wear on her forehead and of the blood that he did; the orange of the sun that he had seen set in the west of three continents; the yellow of ghee and of McDonald’s french fries which he had secretly come to love; the green of the trees on his mountain home and of Ireland’s grassy hills, the blues of the Indian ocean and of Claire’s eyes.

He stopped, opened his eyes, looked at Ganesh again, the ugly, large-nosed elephant man who reportedly made a wonderful lover.

Why were Claire’s eyes entering his mind?

What did they have to do with doors, with open doors?

He closed his eyes again, tried to concentrate.

He saw Claire there, again, with the blue of her eyes through the words of the poem he had memorized as a student in Lucknow, when he was just beginning to learn about love, in his own body:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

He heard Caitlin stirring in bed and opened his eyes again, and then shut them quickly out of a sense of guilt at having allowed Claire to enter his thoughts like this, during his meditation, on this day so obviously full of anxiety for Caitlin that he could see it on her face already, through the dim blue light before dawn.

He skipped purple and went straight to white to complete his meditation, remembering the white on white embroidery his great-grandmother did, which she continued to do even up until the day of her death, the stitchery so delicate that it might have been done by the tiny translucent spiders that lived in the crevices of the bark of the oldest trees in the forest.

He then sent a blessing to those spiders and those trees, and to his great-grandmother, his father’s mother, and another to his mother’s mother, also in the spiritworld, and to his own mother, and to all his aunts, and to all the mothers he knew, including Claire, and Caitlin’s mother, whom he had never met but who, he knew, could probably use some extra blessing on this day.

And he finished by giving light to Caitlin, who was not a mother, and so lacked the wisdom of one; he prayed that the water surrounding her now in the shower would stay with her all day and into the night, as protection, as comfort, as something clear and pure and clean and white and full of wisdom.